Saving The West Alla Prima

Dissident Jazz, Bob Ross, and Staying Proactive in a Deactivating World

If it wasn’t for the undeniable state of the world, I would’ve gone into the business for myself ages ago, and I’m not just talking about freelancing. To build something of meaning, of integrity, something that is at once the product of your vision and sensibilities, but also something you hope contributes culturally in fighting back against the rot of the modern world, is a lifelong commitment that shouldn’t be squandered on idle thoughts about miniscule problems. And yet, like a heap of parsley stuck in your teeth, I find myself picking through all the small stuff.

While it’s tempting to have made a “Stop the Indie Infighting” article in light of the collective unfurling of everyone’s sanity and sense, I’m holding off because I am in no position to run around wrangling people for a well-earned smack upside the head. Don’t fret though, that can of worms will be touched on later down the line.

No, my main issue at the moment is a matter of gross over-intellectualization of the arts by way of ourside™ and how you, dear reader, can help make things better without having to triple-guess your aesthetic preferences. And it all starts with a music genre.

Something quite recently got in the craw of certain dissident types: jazz. That uniquely American artform born from a cocktail of classical, spirituals, ragtime, and blues, where improvisation and experimentation melded with popular melodies and consummate musicianship on the parts of players and singers alike.

Now, not liking jazz in and of itself is not a problem. In fact I’ll go one step further and say that I detest taste policing. It’s the reason why my article on curation explicitly stated, “we’re all our own animals with our own ways of being, our own tastes, and our own approach to both our crafts and our support of others.” My goal was to encourage everyone to try all sorts of modes, genres, and artists, and to come to their own conclusions about their tastes, aspirations, and inspirations, and I stand by that sentiment. You can love or loathe jazz all you like, so long as you, in your heart of hearts, gave it a shot and were the ultimate arbiter of your own tastes.

But that’s not what I’m seeing.

When I hear people going on about jazz being a “failed genre,” deriding it as another example of “modern art” slop, with the quiet part outload being this insipid assumption that the entirety of the genre is just free jazz with no regard for harmony, rhythm, or melody, what I’m seeing is not “some people just don’t like it.” There are people who are actively attempting to dress it down from an intellectual perspective, and have become the town elders from Footloose.

This isn’t the first time I’ve seen this brand of nonsense before. From Michael Knowles’ little hand grenade a ways back bitching about Picasso moving away from realism towards cubism to this general lumping in of modernist art with postmodern art, ourside™ seems to have a preoccupation with trying to reconquer the aesthetic world not by reminding us of the beauty of classical, romantic, and baroque artistry, but by trying desperately to get every genie of the past century back in the bottle. And I’m here to tell you that not only can you not, but that in order to revive the classical aesthetics you so seek, burning every bridge back to the gallery is the last possible way you should do things.

First things first: the key to modernism is in knowing that it exists in contrast to classical standards, with those standards held as prior knowledge. Jazz gains its complexity and license to experiment from a musician’s ability to comprehend theory as laid down by Western classical doctrine. Cubism is a stylized distortion of form, established by artists who had to be able to understand form in the first place. On balance, modernist movements emphasized individuality and freedom of expression in their pursuits, looking to break away from conventions of their time, but often still working within frameworks established by the canons of their day. The surrealism of Dalí still relied on distinct and recognizable iconography, morphed and distorted into a symbol-laden tapestry of malformed objects and spaces existing in impossible arrangements. The clocks may be melting, but they are still clocks.

I make this distinction to emphasize that, while postmodernism (as its name suggests) was the phase that followed, the difference between the two in terms of value is night and day. The former understood that a world came before it, and that many of its practitioners came from that world. You cannot have impressionism without the Romantic era. You cannot have jagged-edged German expressionism in cinema without the knowledge of Chiaroscuro that dates all the way back to the Renaissance.

On the flip side, postmodernism does not care what came before, does not care what will come after, and does not care what is under its nose. It is a movement founded on questioning everything and answering nothing. There is a capacity for beauty in modernist work, but I wholly concede that it may not be to everyone’s liking. On the other hand, there is a borderline nonexistent capacity for anything resembling beauty in postmodernism, and it is no wonder that we have been treated to the deluge of minimalist nonsense and baseless performance art that inspires little more than the modern artist’s own ego. The risks taken by modernism had weight because they stood against the backdrop of centuries of traditional artistic practice. Postmodernism holds exactly zero weight because it does not acknowledge that the standard was there at all, or that any standard should exist. After all, nothing holds any inherent meaning, right?

All of this is to say that anyone hoping to revive the dying culture before us who goes on harping about jazz, cubism, and these other modernist inventions are barking up the wrong tree. Not just because these are forms and aesthetics that have held their own in the decades that followed, but because jazz need not fail in order for a great RETVRN to succeed.

The key to reviving classical aesthetics at this juncture is in equal parts practice and appreciation. Now, ourside™ seems to have the appreciation front locked down nice and tight (throw a stone, hit a Michelangelo profile pic), it is the practice front that seems to have bottled a lot of people up. Looking at centuries worth of tremendous fine art, literature, and music, and pining for more to be made, yet it seems that all the levers of production are perpetually out of reach. I described what follows as “academic zealotry,” the idea that you can will this revival through just appreciation and the browbeating of “modernity.” This is where poor old populist me who’s making the weird “furry” speculative fiction magazine tells you: if you want something done, and no one’s around to do it, get up off your ass and do it yourself.

If that means you having to spend years mastering a craft and honing skills, so be it. If that means you learn a grand repertoire of classical compositions so you can pick up their conventions before writing music, then so be it. If that means you stress, sweat, fail, and try again to take that lump of clay and at least make a pot out of it before you try to capture the essence of a man in stone, so be it. Not everyone will have the talent, but some of you will and some of you will be fine enough learners to go that extra distance and become that great, exciting writer of symphonies or sculptor of resplendence. You will work and strive to attain that purity through force of will and willingness to come up from the ashes of your failings and try, try again.

When you haven’t an institution at your back, nor a system willing to educate you, you have to take matters into your own hands, and the sad truth is that complete recapture is not happening anytime soon. While what I’m promoting also demands a great deal of time and dedication, the difference is in the rate at which the action can effect change. A long march back through the institutions is fraught with bureaucracy, backdoor politicking, and a million fail-safes the Cathedral have set in place. Not that it isn’t worth trying, but that it may take many more decades than people are aware of. Whereas today, it is now easier than ever to share, proliferate, and even profit on your own creativity and bring it to those who seek it.

It is at times like these where you learn who really wants shit done; the man who will put money where his mouth is and make something of himself, or a man who will spend the rest of his life writing diatribes into the void. If anyone tries to spin this practical-minded pitch as some kind of Pollyanna solution that “simply won’t do,” all I have left to say to you is this: would you rather spend the rest of your life worshipping the dead, or would you like to make them live again? And live through the work forged by your hand?

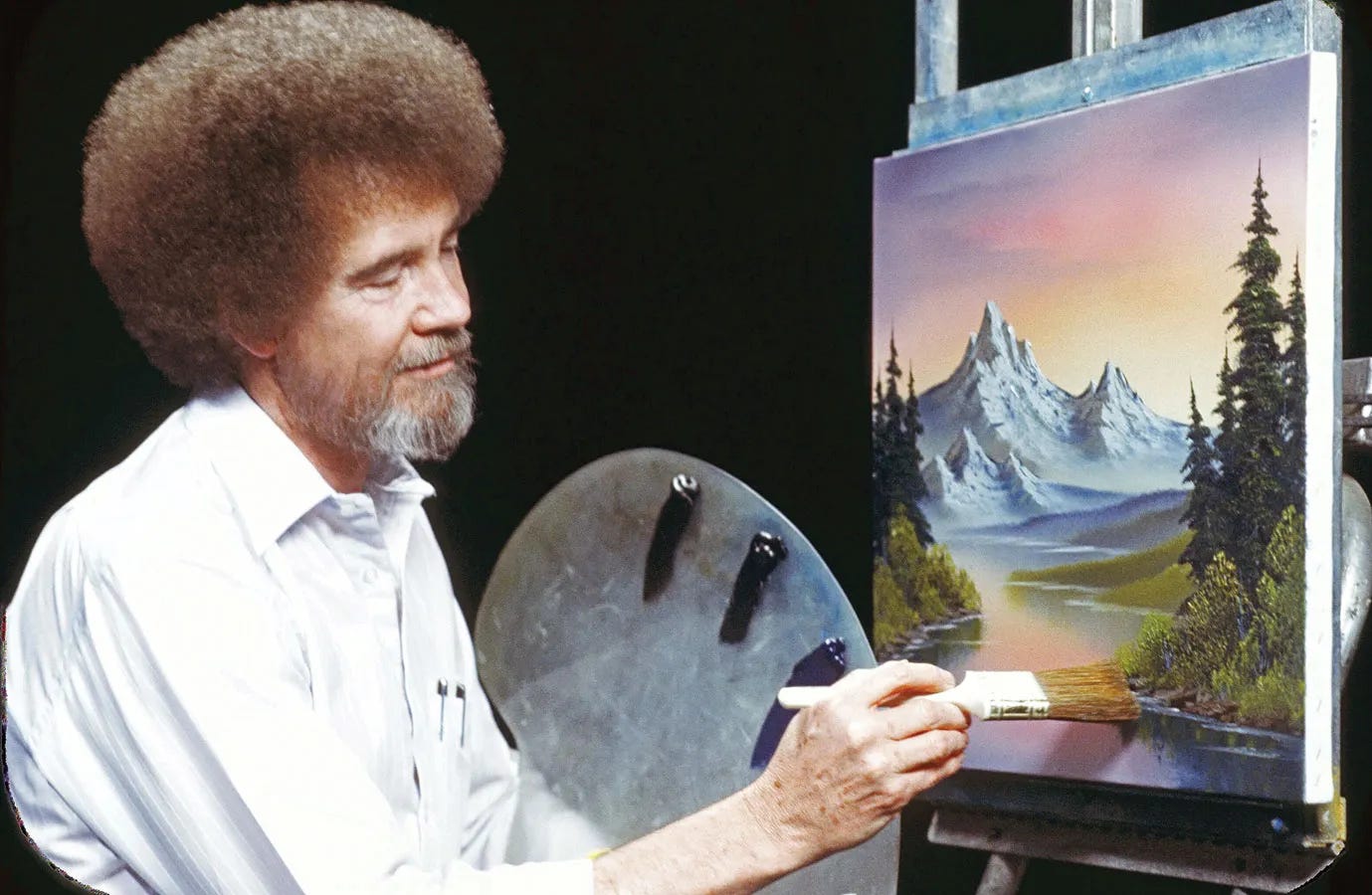

Here’s where Robert Norman Ross comes into play.

From his soft-spoken Southern voice to his iconic perm to his breathtaking ability to turn a canvas of white into a dazzling landscape in a half-hour’s time, Bob Ross and his beloved PBS program The Joy of Painting not only picked up where German painter Bill Alexander left off when his Emmy-award winning series The Magic of Oil Painting went off the air in 1982, but would go on to become a complete pop cultural phenomenon. While many will focus on the cult of personality arrayed around Ross himself, one that persists to this day, what many overlook is how, for over 10 years straight, Ross popularized the alla prima technique to millions after having learned from Alexander personally upon discovering his show.

Alla prima (Italian for “first attempt,” also known as wet-on-wet) is a style of oil painting where the artist applies wet layers of paint one on top of the other, working fast to keep ahead of the previous layers as they dried. Alexander and Ross both applied a base layer across the canvas, and would work fast in their half-hour to paint landscapes without any prior sketching. Minimal paint mixing would be necessary as the wet coats would blend easy on the canvas, resulting in seamless skies and richly textured foreground and background objects like trees and mountains. The end result can best be described as the Hudson River School by way of impressionism. The implication of rich detail is there, but is accomplished through swift action and careful blending to create said details.

While Ross’ instructional program might suggest a “paint-by-numbers” attitude, the quick-thinking necessary to accomplish the end product often lead to Ross emphasizing that viewers should choose to express themselves however they saw fit in the creation of the painting, reinforcing that what he was teaching was a technique, not a coloring-book approach to painting. Placements of finer details and the broader backdrop were all left up to the viewer, provided they adhered to basic concepts like consistent lighting.

I highlight all of this to say that it can be done. You can produce fine art in an efficient manner, and it needn’t be kitsch or amateur-hour playacting. Not everyone will have the knack, but there will be some who do, and some who take to it like a duck to water. Some who will finally find some purpose in their lives, and that ultimate purpose being the rekindling of beauty in their own way.

Now, let’s make this all painfully clear: this message is specifically for those who have lambasted the decadence and decay of the art and aesthetics of today, and should do something about it. We can spend decades reidentifying problems that have already been exposed, but that exposure means little if there’s nothing to be done to usurp these harbingers of ugliness.

I’m not talking about your average Joe or Jane in flyover America who are sick to death of the pabulum of Western entertainment. Hate to break it to you kids, but the normies aren’t coming to save you anytime soon. I believe in the Iron Age and in the work of NewPub and in the independent game devs, musicians, comic creators, and so on, but the truth is that we need to build up that parallel economy before we can reach the masses. These things don’t happen overnight.

I’m also not talking about overt political activists who, if we’re all being perfectly honest, should stay away from the levers of cultural restoration simply because they’ve thrown their lot in with understanding the levers of power more thoroughly.

I am talking to the people who know there is a problem in the world of the arts, see there are solutions, but have either learned their helplessness so deeply or hold a genuine ignorance of the road to that solution. I’m talking about the ability to be proactive in a deactivating world, and to work towards the restoration of these finer things in life in an increasingly decadent time.

Things are bad. As I said to a writer friend the other night, it's going to keep sucking until the straw starts making that godawful sippy sound. But you can't spend that time demoralized and holding out for the pendulum to swing back in the nick of time. Vote with your wallets, your ballots, your minds and hearts, and with your hands. Never give in, never surrender. When your institutions have failed you, you're going to have to learn what it is you're missing. For some that's survival skills, for others that's being able to recognize, relate to, and produce beauty. It won’t happen in a day, a month, or even a year, but it will happen if those who truly, desperately wish it to be so, will get up, go to the canvas, and work their ass off to learn, fail, try again, and succeed.

Will outside forces and political changes hasten this reviving of culture? Yes. But someone's got to keep the lighthouse burning in order for the ships to know which way to go. That's what we're doing. Right now, morale is in frighteningly short supply. That's where we come in.

I have faith that the communities encompassed and arraying around the idea of the Iron Age will help on the front of entertainment. They may bring us the pulp heroes of our time, spinning stories of great heroism and daring and adventure at a time where morale needs boosting, and chaining yourself to “the discourse” will only bring a heaping helping of misery. But the Iron Age cannot compensate in the realm of fine art. It just can’t.

We in this sphere are dealing in popular arts and mediums that have traces of lineage back to the masters, but their current forms do not represent that same purity we find in a great etching or a fine sculpture. The popular arts will be nourishing to the masses when they arrive, but entertainment alone is not enough. We also have a penchant for letting egos and menial bullshit supersede the cause we’re all working towards, but I’ve come to the simple conclusion that you have to let it blow past you, and keep going. Those determined to make an ass of themselves will either fade away in due time or retreat to their own communities. Those on the frontlines will keep fighting like hell ‘til we win.

The other truth of the matter is you can’t just legislate the fine arts back into being great either. You can hope and pray that 2024 produces a president who isn't liable to slip and fall onto the little red button in a dementia haze, and lobby him for better grants and initiatives to beautify architecture, but that can be a long 12 months, and even longer still when more prescient issues are on the ballots and weighing on the minds of millions.

All this is to say that we are living in an era where direct action is our only true course of action. We can’t wait any longer. We are starved, and may go on starving. And while I believe strongly in remembering, learning from, and appreciating the marvels of the past, the creation of beauty cannot belong to the dead alone. Beauty must replenish the souls of today, and must be drawn from and to the souls of today. I can’t think of a better way to do it than to take up that centuries-old banner and prove that, yes, beauty cannot only be appreciated today, but it can be made TODAY.

If you’re wondering where the hell Harlan Ellison fits into all of this (besides the drinking game), I’ve got a quote from one of Ellison’s appearances on Tomorrow with Tom Snyder. In response to the perennial complaint of “I have this great novel and nobody will buy it,” our mensch of the hour kicks down the door with this:

“There are no great unpublished works in this country at the moment. And if there are, it’s because people don’t have the guts to send them out to market. And that’s all it takes.”

Today, it is easier than ever to bring that great work to market through tools of self-publishing and self-distribution. Getting it seen and read and appreciated may be another kettle of fish, but the truth is you can bring it on. And while these tools have often been wielded in the name of more popular forms of art, I do believe that, when galleries are few and the Ivory Tower is crumbling, these tools can be used to bring fine art into the world just as well.

Get busy.

Well said. I am going to avoid merely restating your points, which are excellent, and bring up the one thing I think you missed about outside™️ (I like that): too many think they every single artistic thing from 1900 onwards has been a government-funded, artificial, top-down ploy to “destroy the West.” And probably created by the dreaded Jews to boot. This makes it impossible to have any sort of meaningful conversation about culture with certain types. I can only imagine it’s worse if you’re Jewish and trying to talk to them—it’s bad enough as a Christian.

You have to meet people where they are and they are not at the point of RETVRNING. Nor should they be. Nor should anybody be. Link your new art to the past, build upon it. Don’t try to recreate it. Now is a different time than then. We can be informed and inspired by the past but trying to ape it can only create a facile simulacrum. To use a music analogy, jazzers put their own spin on standards all the time. That’s the way to do it. Cream and Led Zeppelin weren’t “blues bands,” they took blues songs they loved and reconstructed them in their own idiom. That’s the way to do it.

Dan Simmons didn’t try to write his own version of Dune, or even his own version of the Canterbury Tales. He threw his influences in a blender and filtered Jr through his own ideas during his own time. That’s the way to do it.